“Chance is a word void of sense; nothing can exist without a cause.” These are the words of Voltaire, a famous French philosopher and writer who believed that everything follows a “secret plan” and that there is no such thing as indeterminism. For about a century, however, many physicists have been advocating the idea that the world in its smallest follows pure, objective coincidence, a coincidence that we have never seen in our everyday life, because we know subjective coincidence only.

What is a subjective coincidence?

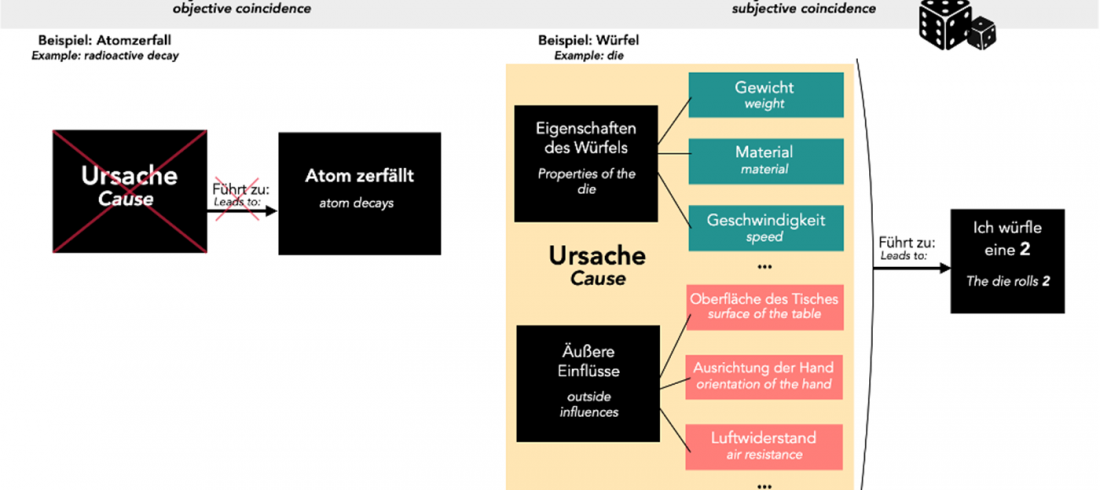

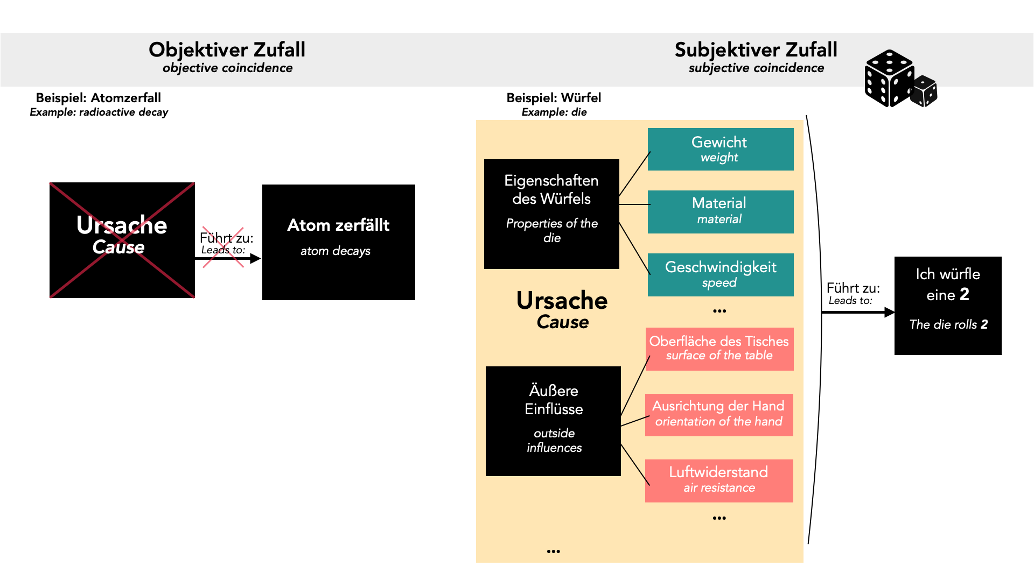

According to the dictionary, chance is an unexpected circumstance, something that was not foreseen, that was not intended. This applies to both the objective coincidence and the coincidence that we know, the “subjective” coincidence. A subjective coincidence (see figure 1) is basically not a pure coincidence, but an event that is perceived as “coincidence” from a subjective point of view. It only arises because of our ignorance, which makes us perceive events as “surprising” and “unexpected”.

Throwing a die is an example of subjective coincidence. Two sides of a die have an equal chance of being rolled at the table as long as the die is a “fair” die. Nobody knows what the next number one rolls will be. However, a number of factors determines which number is actually rolled next. So you could determine the result in advance if you knew the properties of the die such as its speed, weight, material or the orientation of the hand, the properties of the surface of the table or the air resistance.

The same principle applies if two people happen to meet in a restaurant. Car traffic, weather forecast, reviews on the Internet and reports on TV, radio forecasts, etc., will most certainly have brought the two people to the exact same place at the same time. Even if it seems as if both people purely met “by chance”, there are still a number of events and details that lead to the phenomenon, but we cannot perceive or identify them directly.

What is an “objective” coincidence?

An “objective” coincidence is a coincidence, which does not depend on any parameters/factors, it is not determined by any cause — which means it is fully independent (see figure 1). Therefore, the exact same situation can result in different outcomes. This is also called objective indeterminism. This kind of coincidence — even if we know all the parameters — can never be exactly predicted: it is the perfect, absolute coincidence. To explain it with the words of the Austrian scientist Phillip Frank, the objective coincidence would be an event that is “a coincidence with regard to all causal laws and therefore does not appear anywhere as part of a chain”. But as seen before, the objective coincidence could only be observed in quantum physics.

One example for the objective coincidence is the radioactive decay. Let’s imagine a single atom, which is about to decay. We know the probability with which the atom will decay in the next 5 minutes, but if the decay will really take place in the next 5 minutes or when exactly it will take place is unclear and cannot be predicted by anything. There is no objective reason for the timing of the individual decay. The atom simply decides “like that” at some point to decay without any cause, so the event is fundamentally indeterminate.

It is still unclear if there are hidden parameters that determine the moment of the decay or not, i.e. whether there is a cause for such processes in the quantum world that is simply not known. The theory that there are hidden variables that are supposed to guarantee a deterministic sequence of events, however, has hardly any supporters for a variety of reasons.

The problem triggers debates about whether the world is fundamentally deterministic (predictable) as it is described by classical physics or whether it obeys purely random principles at its core, as is currently suspected in quantum physics.

The theory of indeterminism is also advocated by the Copenhagen interpretation of quantum mechanics, which declares many events in quantum mechanics (= quantum physics) to be fundamentally indeterminate (i.e. these happen objectively by chance, such as radioactive decay).

What are interpretations of quantum mechanics actually?

When we hear the verb “to interpret” we usually think of a task that is given in language courses — a horror for many, a hobby for some, which has to be answered with a given text excerpt or more texts excerpts. When someone interprets a text, they question and reflect on the content of the passage and the author’s views. Hence, they try to see the “big picture”, what lies behind the lines and connects all the details of the excerpt in a logical way.

The same thing happens when interpreting a painting: the observer searches for the symbolic meaning behind particularities of the artwork such as light conditions, colours and shapes to later find and explain all the connections between them.

Interpretations of quantum mechanics work similarly: They attempt to explain how all the different concepts of quantum mechanics are connected and what they mean for our reality. In short, they are physical theories that try to describe the processes in the microcosm. Since a lot of principles of quantum physics (or quantum mechanics) are not entirely clear yet, there are a lot of different interpretations.

What is the Copenhagen interpretation?

The Copenhagen interpretation was created in 1927 by the Danish physicist Niels Bohr and the German physicist Werner Heisenberg during their collaboration in Copenhagen. The Copenhagen interpretation is based on the probability interpretation of the wave function proposed by the German mathematician and physicist Max Born. It is one of many interpretations of quantum mechanics. The more modern variant of the Copenhagen interpretation, called the Ensemble interpretation, is the most widespread interpretation of all.

It contains several principles and theories related to quantum physics, but we will only look at the most important ones below.

The laws in the world of the microcosm and those of the macrocosm differ fundamentally: In classical physics, which means in the world of the macrocosm, all laws are generally considered to be deterministic, because we can make exact predictions for any measurable physical quantity (like angle, mass, temperature etc.), if we have enough information at our disposal. Moreover, every object is in a clear, defined state. The location of any object is thus described by its location coordinates as a function of time.

But in the world of microcosm, or more specifically in quantum physics, this is very different. There, the location of a quantum object (for example an electron) is defined by its wave function, which indicates the probability for each possible location of the particle that the particle will actually be found there. Before a measurement, quantum objects usually find themselves in the state of superposition. During the superposition, an object is simultaneously in all of its potential states, which means at the same time at all potential locations; it is so to say “everywhere” and does not take a specific state.

The Copenhagen interpretation assumes that it is the measurement itself that creates the location of the particle, compared to classical physics, where the measurement just determines it. So the first measurement destroys the superposition of the particle. More precisely, the particle “decides” itself “coincidentally” during the measurement what state to take and only then it becomes a particle in a specific location. Which state the particle chooses during the measurement, can never be exactly predicted with all the information we have.

That’s why we cannot make exact predictions for every physical variable in quantum physics, we can only predict it statistically, or more precisely, we can only predict the probability that a certain value or state will occur, but never the exact outcome. For that reason, the Copenhagen interpretation advocates the theory of indeterminism, which we have seen already.

Erwin Schrödinger also deals with the Copenhagen interpretation and its principles in his thought experiment Schrödinger’s cat. In the following we will take a closer look at his thought experiment.

The experiment was devised in 1935 by Erwin Schrödinger, an Austrian physicist and scientific theorist. He is one of the founders of quantum mechanics and received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1933 with his colleague Paul Dirac, a British physicist.

What is a thought experiment and what is the goal behind Schrödinger’s Cat?

A thought experiment is generally an experiment that is only carried out in the mind. It is a tool that supports, refutes or illustrates certain theories.

With his thought experiment, Schrödinger wants to show a major weak point of the Copenhagen interpretation of quantum mechanics in relation to physical reality: it shows the paradox that arises when one wants to use the terms from quantum mechanics in the macroscopic world. In his experiment Schrödinger lets quantum physics “collide” with classical physics, that means, the microcosm with the macrocosm.

What is the thought experiment of Schrödinger?

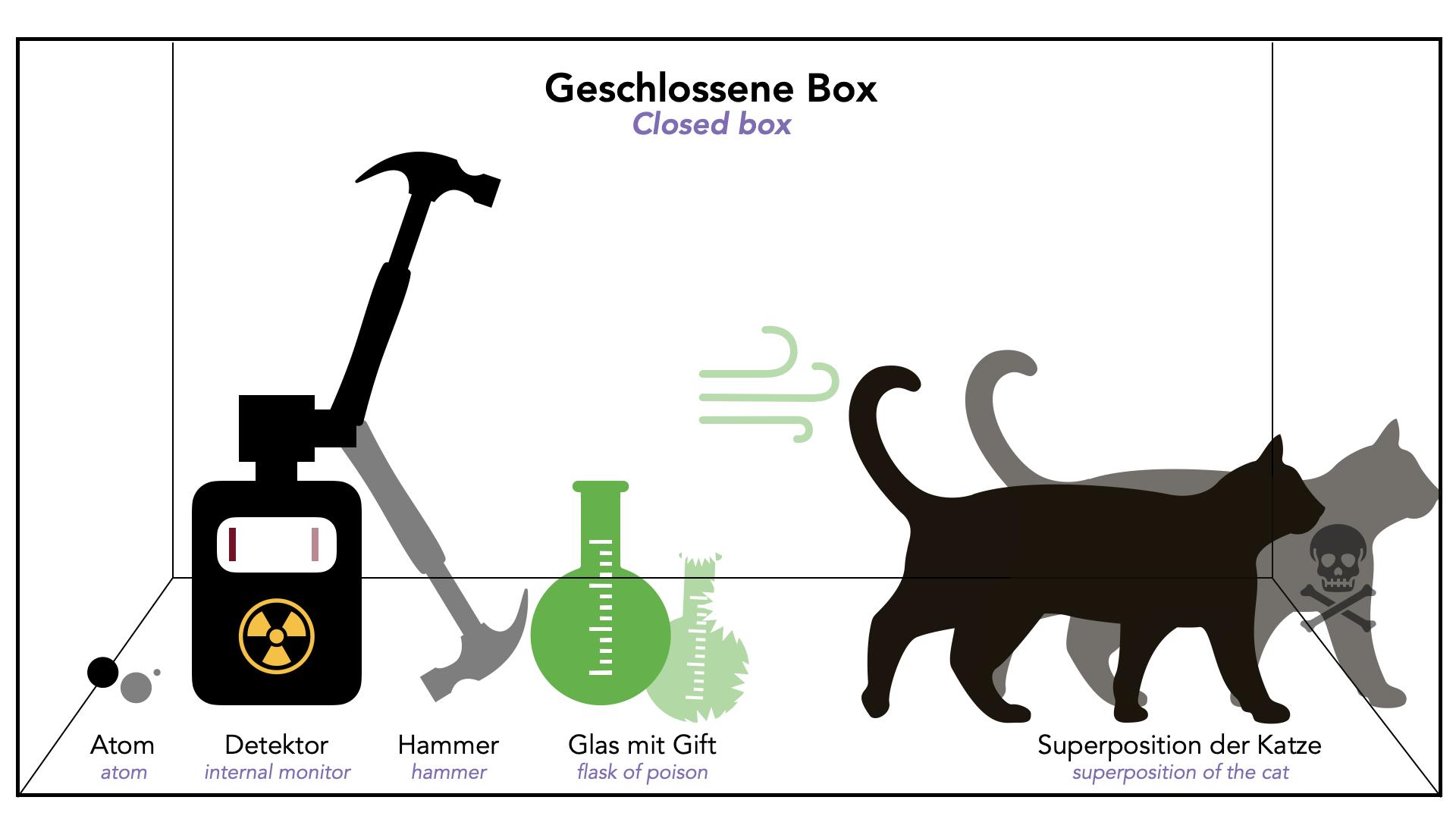

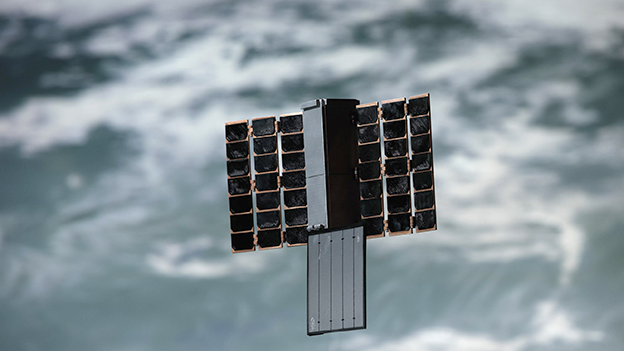

In a sealed box (see figure 2) there are a radioactive atom, an internal monitor, a hammer, a flask of poison and a cat.

Like we have seen already, radioactive atoms have the property to decay over time, but we can’t predict when exactly that will happen. If the atom in the sealed box decays, the internal monitor detects the radioactivity and lets the hammer fall down which then shatters the flask. As soon as the poison from the flask is released, the cat dies.

Now we have two possibilities: either the atom decays and the cat dies or the atom does not decay and the cat stays alive.

We know that the atom is a quantum object and therefore follows the rules of quantum physics. In quantum physics, the atom is in the state of superposition, which we have seen before: it is in all of its potential states at the same time. This means that it is decayed and not decayed simultaneously, as long as we don’t measure it — or in this case, as long as we don’t open the box and look at it. (That’s why the box must be sealed for the thought experiment to work.) If we do, then (according to the Copenhagen Interpretation of quantum physics) the atom is “forced” to choose a state and we would only see one of two potential states: the cat would be either definitely dead or definitely alive.

Thus, as long as we don’t open the box, the atom is decayed and not decayed simultaneously which leads to the internal monitor detecting and not detecting radioactivity simultaneously. Subsequently, the hammer is released and not released, the flask of poison is scattered and not scattered and therefore the cat is dead and alive simultaneously — it would be in the state of superposition, too.

And here is the paradox: it’s perfectly fine for the atom of the microcosm to be in two potential states at the same time, because quantum physics says so, but the cat cannot be in such a superposition, it would contradict the rules of classical physics and our own everyday experiences in the macrocosm.

Schrödinger’s thought experiment therefore represents one of the greatest problems of modern physics: bringing the laws of the microcosm together with those of the macrocosm. There is still a lot of research to be done for the physicists of today and tomorrow…

About the Author:

Catharina Orasch | currently attends the Lycée Français de Vienne. She applied to the Science Academy Lower Austria in order to dive deeper into the topic of „space“ and meet with other interested students. Besides science she is also interested in writing; she can combine both of her interests while writing blog posts.

Quellen:

- Vortrag von Anton Zeilinger

Und zur Vertiefung des Wissens:

https://www.phyx.at/was-ist-zufall/

https://www.chemie.de/lexikon/Quantenmechanik.html

https://www.chemie.de/lexikon/Kopenhagener_Deutung.html

https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Interpretationen_der_Quantenmechanik

https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Erwin_Schrödinger

https://de.universaldenker.org/lektionen/211

https://www.spektrum.de/lexikon/physik/quantenmechanik-und-ihre-interpretationen/11871

https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gedankenexperiment